The Hidden Risk in Aerospace Structures: Process Drift Between Simulation and Manufacturing

- kaan deniz

- 8 hours ago

- 2 min read

If you think most structural failures happen on a test flight, you're missing the real story.

The trouble usually starts long before the aircraft leaves the ground.

You sign off on the FEA. Margins look solid. Every load is accounted for.

Then you walk onto the shop floor.

Now things get interesting.

Laminate thickness is off by 0.2 mm.

Fibre volume fraction refuses to stick to the plan.

Porosity wanders across the part like it owns the place.

Cooling rates decide to experiment with crystallinity.

But it's fine, right? All "within tolerance."

Except your stiffness is off.

Your model says the structure is robust, but reality has other ideas.

This is how late surprises sneak in, well after you thought the hard part was done.

And with composites, it's never just the geometry or loads that trip us up.

It's everything nobody wants to talk about.

Temperature swings mid-cure.

Pressure that drifts on a Friday afternoon.

Crystallisation kinetics are doing their own thing.

How the tooling flexes when you least expect it.

Pretend these don't matter, and your model is a best guess at best.

On paper: everything checks out.

In practice: the risk is hiding in plain sight.

There's a gap between what we think we've built and what's actually rolling out of the hangar.

That's where the real programme risk lives.

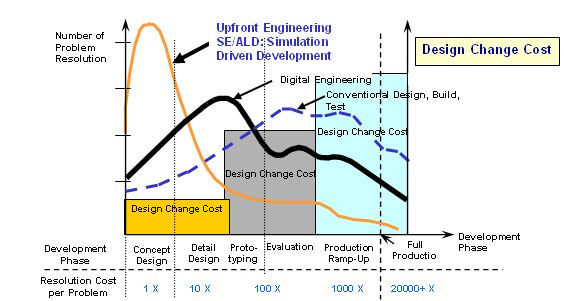

The next leap in aerospace engineering isn't about smarter FEA or fancier dashboards.

It's about finally connecting manufacturing variability with structural modelling.

Thermo-chemo-mechanical simulation isn't an academic luxury.

It's the only way to see risk before it bites.

Here's the brutal truth:

Uncertainty in process

→ changes material properties

→ shifts stiffness

→ redistributes loads

→ creates project headaches that make grown engineers groan.

Most will keep blaming the analysis tools or the design specs.

Few will admit the real enemy is process drift.

We can't afford blind spots. Our models are only as strong as the weakest link in manufacturing.

Want fewer surprises? Bring process variation into your analysis. Stop pretending it's background noise.

Ignore this at your own risk. Programme overruns and late fixes aren't bad luck. They're baked in when you treat the shop floor as a black box.

Engineering isn't about surviving the test anymore.

It's about understanding where the real physics change as soon as someone fires up the autoclave.

If you've ever had an unexpected "within tolerance" part give you grief, drop a comment.

Let's see how many of us have learned this the hard way.

It's time the industry faced up to it.

Comments